Bioluminescence Beyond Aesthetics: The Hidden Purpose of Fungal Light

When evolution invents a nightlight and refuses to explain itself

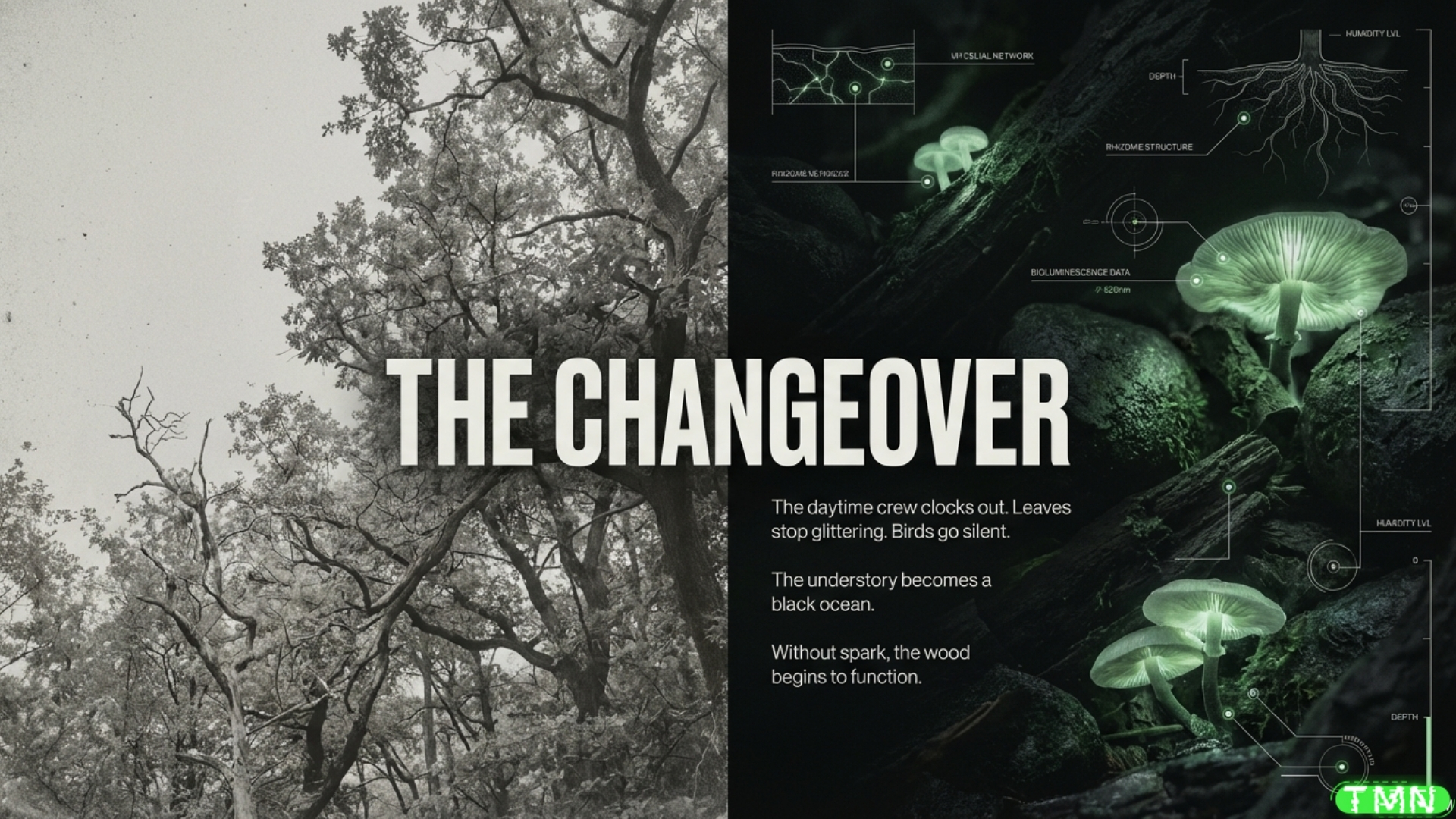

At night, parts of the forest don’t go dark — they glow. Bioluminescent fungi emit cold green light through a highly efficient chemical reaction that may function as both metabolic detox and ecological signaling. What looks like woodland ambiance might actually be evolutionary strategy. And once you realize nature doesn’t waste energy on aesthetics, the glow stops being magical and starts being deeply suspicious.

Light in the Dark Forest

At midnight, the forest reorganizes itself. The visual hierarchy collapses, color drains out of the canopy, and the understory becomes a study in gradients of black. It is in that sensory vacuum — when vision becomes scarce currency — that a fallen log begins to emit light. Not a flare, not a flicker, but a steady, cold green glow that feels less like illumination and more like intent.

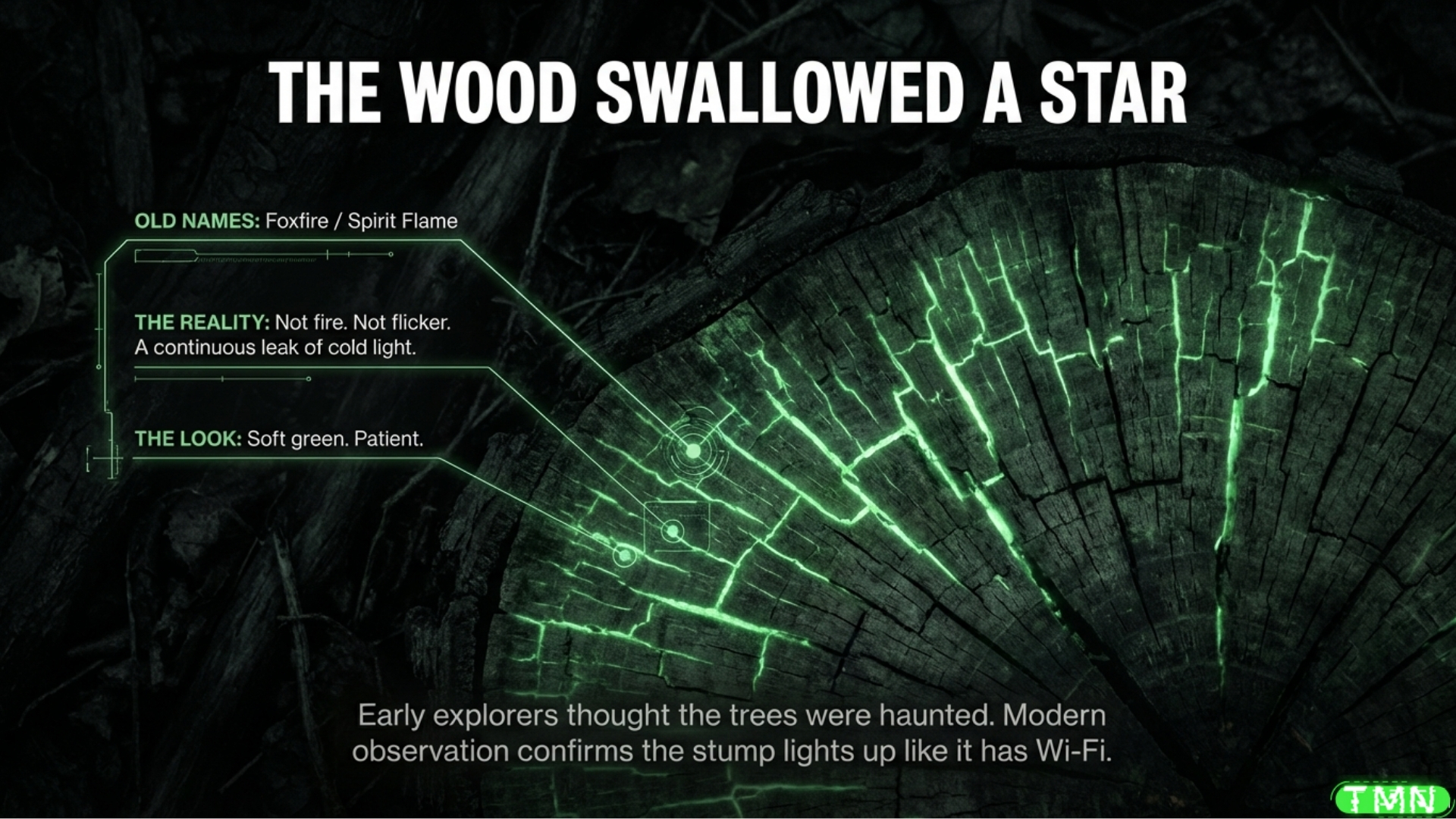

For centuries, humans interpreted this phenomenon through whatever supernatural framework was locally available. Foxfire in Europe. Spirit flame in parts of Asia. Haunted timber to early naturalists who had not yet met oxidative chemistry. And frankly, that reaction is understandable. When dead wood lights up in the absence of flame, your brain reaches for ghosts before it reaches for enzymes.

Modern science explains the glow through a luciferin–luciferase reaction unique to fungi. The chemistry is real, measurable, elegant. But explanation does not equal interpretation. Because once you accept that light production requires energy — and energy is the most guarded resource in evolution — the obvious question surfaces: why is this fungus spending metabolic currency to glow in the dark?

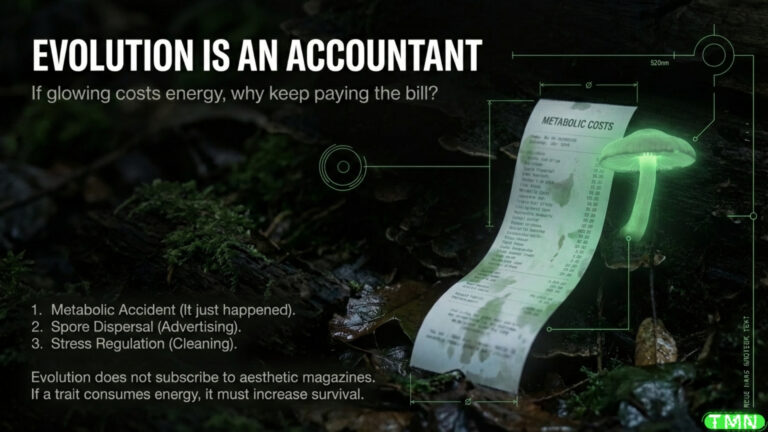

Evolution does not fund decorative lighting. If photons are being produced, they are doing something.

And that is where the glow stops being charming and starts being strategic.

The Chemistry of Living Light

Bioluminescent fungi generate light through a luciferin–luciferase pathway — and yes, the name sounds like we’re about to summon something with horns. “Lucifer” literally means light-bringer in Latin, long before theology gave it a villain arc. In fungi, it’s not a fallen angel. It’s a molecule derived from caffeic acid that emits green light when oxidized by a specific enzyme. Separate lineage. Separate chemistry. Same luminous result — but far more heavenly than infernal.

What makes this particularly interesting is not just that the reaction works, but how efficiently it works. Bioluminescent reactions are often described as “cold light” because they convert a large portion of chemical energy directly into photons rather than heat. Compared to human incandescent bulbs — which waste most of their energy as warmth — fungal light production is metabolically restrained. The glow is subtle, but the chemistry behind it is impressively economical.

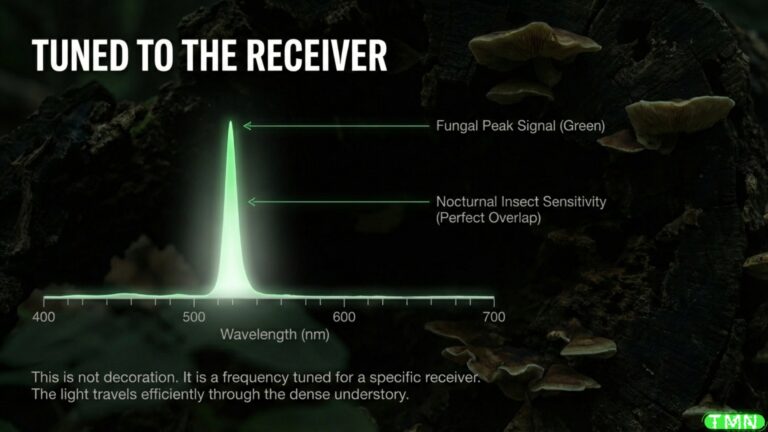

Then there is the matter of wavelength. Fungal bioluminescence peaks around 520–530 nanometers — green light. In dense forest understory, green wavelengths transmit effectively through leaf-filtered darkness. More importantly, many nocturnal arthropods exhibit visual sensitivity near this range under low-light conditions. That overlap may not be accidental.

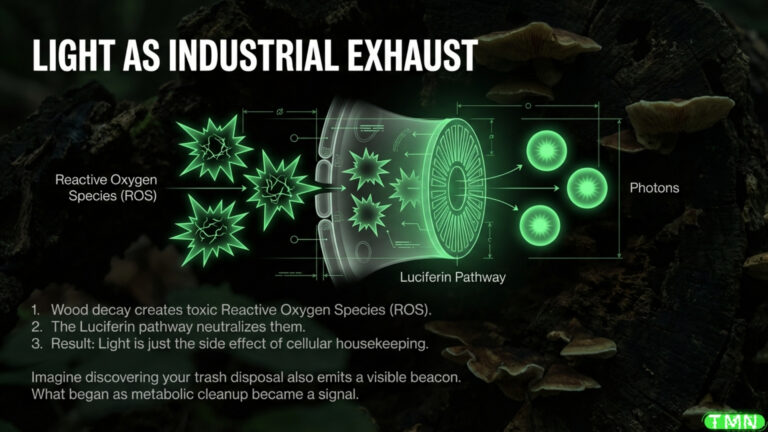

Originally, the luminescent pathway may have functioned in oxidative stress management. Wood decay generates reactive oxygen species, and fungi must manage these chemically aggressive molecules while dismantling lignin and cellulose. If a detox pathway emits light as a byproduct, the glow could have begun as metabolic housekeeping.

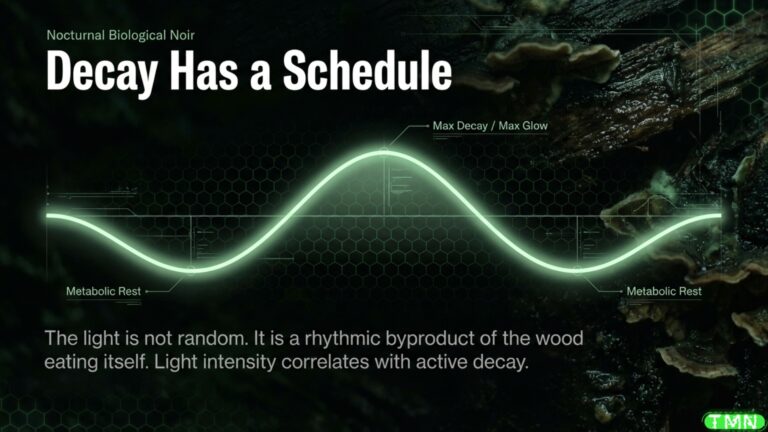

But evolution rarely ignores useful side effects. Once light exists in an ecosystem, organisms evolve to detect it. When insects begin responding to glow, the chemistry shifts from internal maintenance to ecological interface.

At that point, the question changes. It is no longer “why does this fungus glow?” It becomes “who is watching?”

Why Would a Mushroom Pay the Electric Bill?

Lately, humans have been collectively losing their minds over rising electricity costs — data centers multiplying like metallic mushrooms, AI servers humming day and night, headlines about grids straining under the weight of cloud computing. Entire communities are debating kilowatt hours like they’re discussing medieval grain shortages. The modern anxiety goes something like this: Who is using all this power, and why is it costing me?

Now imagine being a fungus.

You’re not running a data center.

You’re decomposing a log.

And yet — you, too, are paying an energy bill.

The difference is this: nature does not subsidize inefficiency. There is no bailout for wasteful glow.

Energy in biology is survival currency. If a trait persists across generations, it must contribute — however subtly — to reproduction or resilience. Bioluminescence appears in specific fungal lineages rather than uniformly across all fungi, which tells us immediately that this glow is not random metabolic leakage. It is shaped by selective pressure. Evolution has looked at the bill and said, “Fine. Keep it.”

One leading hypothesis proposes that the glow attracts nocturnal insects, which then assist in spore dispersal. Experimental studies using artificial mushroom models equipped with green LEDs matched to natural fungal emission spectra demonstrated increased arthropod visitation compared to non-luminous controls. Reduce the glow, reduce the traffic. In a dense understory where wind currents are weak beneath the canopy, hitchhiking spores on curious insects could significantly improve dispersal range.

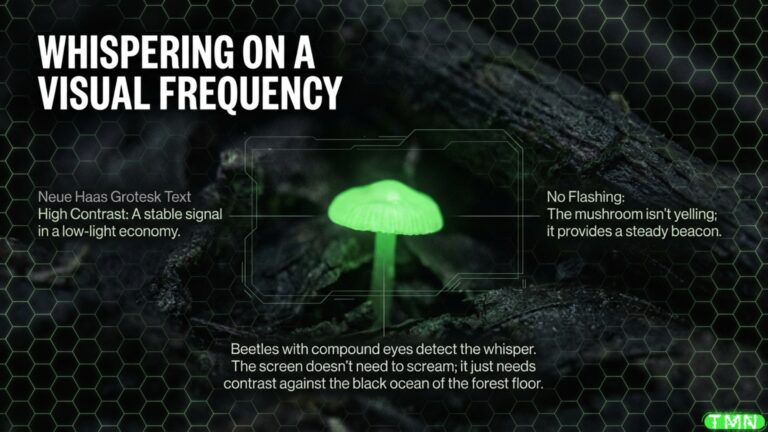

Notice something subtle here: the glow is steady, not flashing. Flashing is theatrical. Steady is functional. Insect compound eyes detect contrast in low light environments; a constant green signal against a dark background is easier to locate and approach. The fungus doesn’t need spectacle. It needs visibility.

Another hypothesis focuses on metabolic timing. Some bioluminescent fungi exhibit circadian regulation in their light emission, with brightness fluctuating over daily cycles. If luminescence intensity correlates with peak metabolic activity — when wood decay is most active and spore production is highest — the glow may function as an indirect indicator of resource availability. In other words, the light could signal, “Now would be a good time to stop by.”

These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive. A pathway that may have originated in oxidative stress regulation during lignin breakdown could later be co-opted into a dispersal strategy. Evolution rarely invents from scratch; it refines, repurposes, and stacks advantages. Detox and advertisement can coexist in the same chemical cycle.

From that perspective, the glow becomes less about spectacle and more about leverage. The fungus is not illuminating the forest for ambiance. It is investing metabolic currency where the return might justify the cost.

Unlike us, it does not complain about the grid.

It simply makes sure the light earns its keep.

The Forest After Dark: Signals We Don’t See

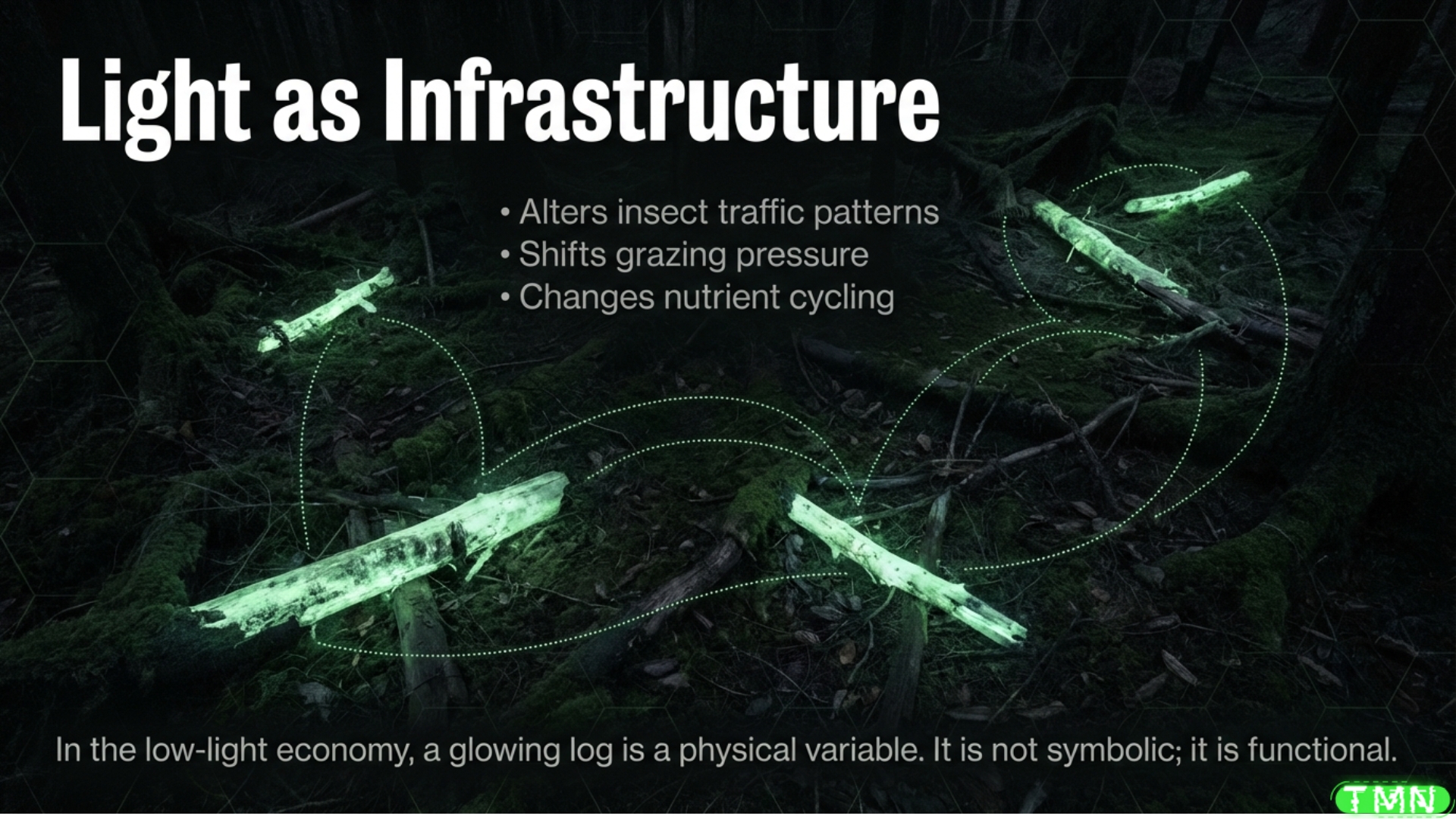

Nighttime forests operate under different rules. The sensory economy shifts toward organisms capable of navigating low-light gradients. Beetles, moths, and other arthropods rely on subtle contrasts and faint spectral cues to orient themselves in darkness. Within that context, a glowing log alters local movement patterns.

Changes in insect traffic influence grazing pressure, microbial interactions, and the distribution of spores. At micro-ecological scales, even small shifts in organism behavior can cascade into measurable differences in decomposition rates and nutrient cycling. Light, in this case, functions as an ecological variable rather than mere visual ornamentation.

Fungi themselves are not passive substrates in this system. Mycelial networks exhibit electrical activity associated with metabolic processes. Although the relationship between internal signaling and luminescence remains under investigation, the possibility that glow intensity reflects physiological state introduces another layer of complexity.

To human observers, the glow feels aesthetic — beautiful against the dark. But insects may interpret it as information. Habitat. Resource density. Reproductive opportunity. Or simply a reliable point of orientation in a visually sparse environment.

Evolution does not optimize for beauty. It optimizes for function.

If the glow improves dispersal, enhances survival, or stabilizes metabolic stress even marginally, that is enough.

🌟 MycoTip the Network! 🌟

themushroomnetwork@vipsats.app

🌀 Myco-Conclusion: Light Without Flame & Evolution’s Quiet Lantern

Bioluminescent fungi complicate our assumptions about what light signifies. We tend to associate illumination with fire, heat, or intention. Here, light emerges from decay without combustion. It is chemistry, not flame. Process, not performance.

A pathway that may have originated in oxidative housekeeping becomes a beacon visible to nocturnal life. A byproduct becomes an interface. A metabolic reaction becomes ecological influence.

Somewhere tonight, a fallen log is glowing. Insects are adjusting their paths. Spores are dispersing. Reactive molecules are being neutralized. Photons are leaving a surface that was once tree and is now fungal network.

No flame required.

Which leaves us, Myco-Patrons, with a deeper question:

How many phenomena we label as aesthetic accidents are actually functional strategies we have not yet learned to decode?

Because if decay can produce light…

What else in nature is quietly signaling while we mistake it for scenery?

Suggested Myco-Articles For You:

Can Mycelium Feel Music? The Answer Might Make You Cry

You’ve heard of plants responding to music. But what if mushrooms—the mycelial masters of the underground

Read More...Zombie Ants in Space? The Cordyceps Invasion Begins

Cordyceps is not your chill adaptogen. It’s a mind-controlling fungal parasite with a flair for drama—and potentially, a future in off-world colonization. This real-life zombie fungus hijacks insect brains, erupts from their bodies, and uses them as mobile spore-launchers. Scientists are exploring its properties for medicine, warfare, and even terraforming....

Read More...Interdimensional Mushroom DJs and the Frequency War of 6092

In the year 6092 (depending on your timeline), the Myco-Verses were rocked by the Frequency War—a battle not of weapons, but of resonant basslines and fungal signal storms. Leading the charge? Interdimensional Mushroom DJs who didn’t play music—they channeled it from the Grand Cosmic Mycelial Network itself. This is their...

Read More...Silent Assassin: Rare Fungus Strikes in Sub-Saharan Africa

A rare fungal killer—Syncephalastrum oblongispora—has just claimed its first documented life in Sub-Saharan Africa. The victim: an HIV-positive patient whose weakened immune defenses were no match for this aggressive mucormycete. This isn’t just a tragic case—it’s a cosmic alarm bell that fungi don’t play favorites. They adapt. They invade. They...

Read More...Myco-Article v1.0.4 [Bravo]

How sporetacular was this post?

Tap a star to send your spores of approval (or helpful feedback!)

Oh no! The spores missed their mark…

Let’s co-create a sporetacular post together!

Share your wisdom—how can we make this more Cosmic?